On the Ground: The Red Crosses of Irpin

Read another dispatch from Project HOPE President and CEO Rabih Torbay, who has been on the ground assessing the devastation in Ukraine.

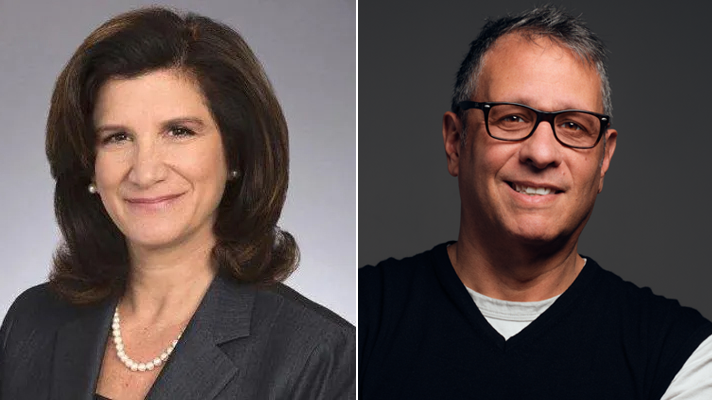

Project HOPE President and CEO Rabih Torbay was recently on the ground in Ukraine assessing the greatest health needs during the war. To learn more about what Project HOPE is doing in Ukraine and how you can help, click here.

We started our morning in Kyiv by meeting with two vice ministers of health. We had to meet outside as the government is working out of a bunker and civilians are not allowed there. The meeting was both good and sad: good, because they told us how much they appreciated Project HOPE and how we are at the forefront sending supplies where they are needed most. But it was sad to see how the weight of the entire Ukrainian health system rested on their young shoulders.

We were meant to leave for Irpin, right outside Kyiv, but we got news that there would be a curfew there for three days as a car had driven over a landmine and two people were killed. When we arrived, the city was empty except for the military, and we could see the destruction along the way. We drove straight to the mayor’s office, where we heard how the hospital had been shelled. Most of its windows had been blown off, and there was damage to the walls.

The mayor gave us authorization to go around the city and document the destruction so the world would know what had happened to his beautiful city. The doctor told us to meet him at the hospital in an hour, as he was going to secure the documentation we would need to go to nearby Bucha.

As we toured Irpin, we saw the impact of the devastation. High rises had been attacked by tank shells and homes destroyed by multi-rocket launchers. There was destruction everywhere. Irpin is a small city outside Kyiv where many people who work in the capital live and commute to their work. Now, almost half of Irpin’s homes have been damaged or destroyed. On one street, all the houses were gone.

We went to the hospital and met the doctor, who showed us the damage. We could see the operating room lights through one of the blown-out windows. The doctor took us to the back of the hospital and showed us a place where a shell had hit the corner of the wall. He told us that two people were killed right underneath, and they buried them right on the spot as they had no time to take them anywhere else. Fortunately, the doctor had evacuated the patients a day before. We also saw a doctor’s vehicle riddled in bullets. The doctor was driving to the hospital when Russian soldiers shot at him from close range. Fortunately, he survived despite being wounded.

As I surveyed the damage, I noticed red crosses had been painted on the hospital walls. I asked the doctor about them. He told me the crosses were there to inform the Russians that this building was a hospital, but that it did not stop them.

In Bucha, the damage continued. We stopped in front of a nice building with a beautiful front yard locked behind closed gates. It was a pediatric hospital, the doctor told us, with damage to the roof and walls. When I asked why the gates were closed, he told us that there were land mines and unexploded ordinances there. Shortly after, we stopped at a maternity clinic and saw a small building next to it that had been burned to the ground with incinerated vehicles in front of it. It was the newborn wing of the hospital.

We no longer had questions to ask, as we did not know what to say anymore.

On the way back from the hospital in Bucha, we stopped at a large church with a towering golden dome. The doctor walked us straight to back of the church without telling us where we were going. He was leading us to a mass grave — what Ukrainians call a brotherly grave. The doctor had dug it himself and laid the first 67 bodies there.

I asked him why he chose this spot. He explained to me that some of the bodies had been in the street for more than a week, and anyone who tried to remove them was sniped down. After days of negotiations with the Russians, they finally allowed him to bury the bodies as long as he dug the grave himself. He chose this spot, he said, as the church dome protected him from the direct line of sight of the snipers. Another 200 bodies had been buried along with the 67 he laid himself.

We were silent, not knowing what to say or do. So many thoughts crossed my mind. I walked away, looking at the church as its shadow covered part of the grave, as if it was embracing its lost children. I wondered how could such atrocities could still take place in the 21st century, and how this amazing doctor could still function after enduring so much.

The doctor then asked us to follow him so that he could escort us outside Bucha. Along the way, he told us that he would drive us through the Street of Death, where most people were sniped down by the Russians. As we drove through, you could see that the road was still red. It might have been our eyes playing tricks on us, but all of us could feel death as we drove through the street.

As we exited the final Irpin checkpoint next to a blown-up bridge, the doctor came down from his ambulance, embraced us, and begged us not to let the world forget what happened in Irpin and Bucha.

We drove back to Kyiv, wondering how the worst and best in humanity could co-exist in one place: how we could be disgusted with what humans can do to one another while also being amazed by how other humans, like the doctors we’ve seen, show the best of humanity, and how we could possibly process what we’ve seen so far.