Keeping Hope Alive for Venezuelans in Colombia

Project HOPE doctors and nurses share their experiences caring in crisis, as more and more Venezuelans arrive to Colombia in need of health services and in search of hope.

Colombia has received the largest increase of Venezuelan refugees and migrants, many of whom need urgent health care — especially maternal, neonatal and child health care. The influx has placed immense strain on the country’s health system, flooding hospitals and clinics with hundreds of thousands of new patients in need of treatment and attention.

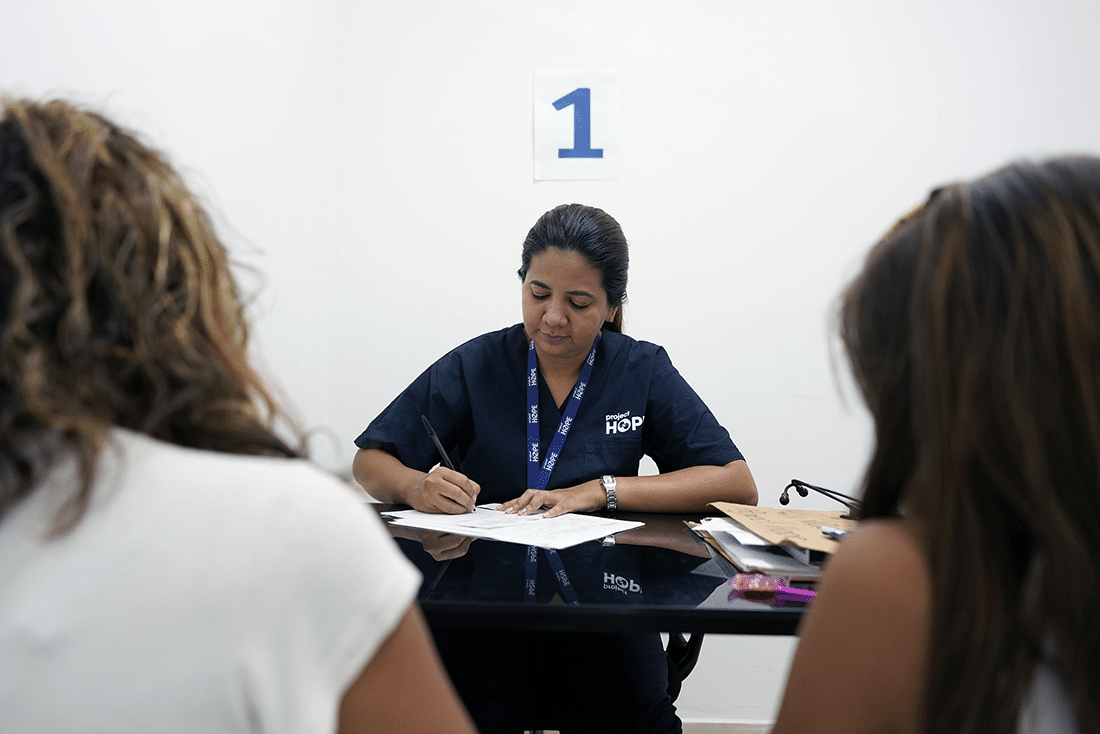

There’s a high stack of patient files waiting for Dr. Myleidy every day — each file tells a story of a Venezuelan refugee waiting for medical care. She doesn’t have enough time in the day to see everyone she’d like to.

Dr. Myleidy, one of several doctors on Project HOPE’s medical team in Cúcuta, works at a clinic near the Simón Bolívar Bridge, an official crossing point between Colombia and Venezuela. Colombia has received the largest number of Venezuelans since the start of the Venezuela crisis — nearly 1.5 million women, children and men — and thousands more continue to cross the border every day, many in search of medicine, medical supplies and health care they’ve been unable to access at home in Venezuela. According to Iván Darío González, Colombia’s vice-minister of public health, Colombia has provided health care services to some 340,000 incoming Venezuelans since early 2017.

Exam rooms have become a safe space of refuge and respite for these patients. Meeting face-to-face with a nurse or doctor is a rare moment of time when they receive undivided attention and care — a rare moment of calm for patients in their otherwise chaotic and distressful daily lives. And it often carries with it an underlying promise of hope: That this might be a turning point to a brighter, healthier future.

Dr. Myleidy treats patients like Roosybelth and her 11-year-old daughter Camila with a gentleness that makes them feel safe as they could under the circumstances. Dr. Myleidy treated Roosybelth for hepatitis B and Camila for diarrhea, most likely caused by poor sanitary conditions in their shelter, where they sleep on the floor, sharing the space with other families. But the impact extends beyond the treatment. Roosybelth and Camila visit the clinic frequently, and have come to know and depend on Dr. Myleidy as a source of comfort and hope.

Dr. Myleidy says it used to be the other way around — that people in Cúcuta used to travel to Venezuela to buy goods and find health services. Times have drastically changed.

At another health outpost, patients of Project HOPE’s Dr. José tell harrowing stories of just how desperate their situations were before being forced to flee Venezuela. Some were working three jobs just to get by. Many recount living without safe water and with limited electricity, only able to cook one meal a day, and being unable to find medicine or health services. By the time they reach Dr. José, they’ve already gone months without the health attention they need:

“There is real contact with the person in need here. The effect of our job can really be seen…on the faces of the people that leave happily — with their medicines, their children having been seen, having received adequate prenatal care, or simply having had a health concern resolved… It’s really gratifying to see people’s faces and to know that we are helping a person that really, truly comes because they need someone to attend to them — someone to understand and be there for them.”

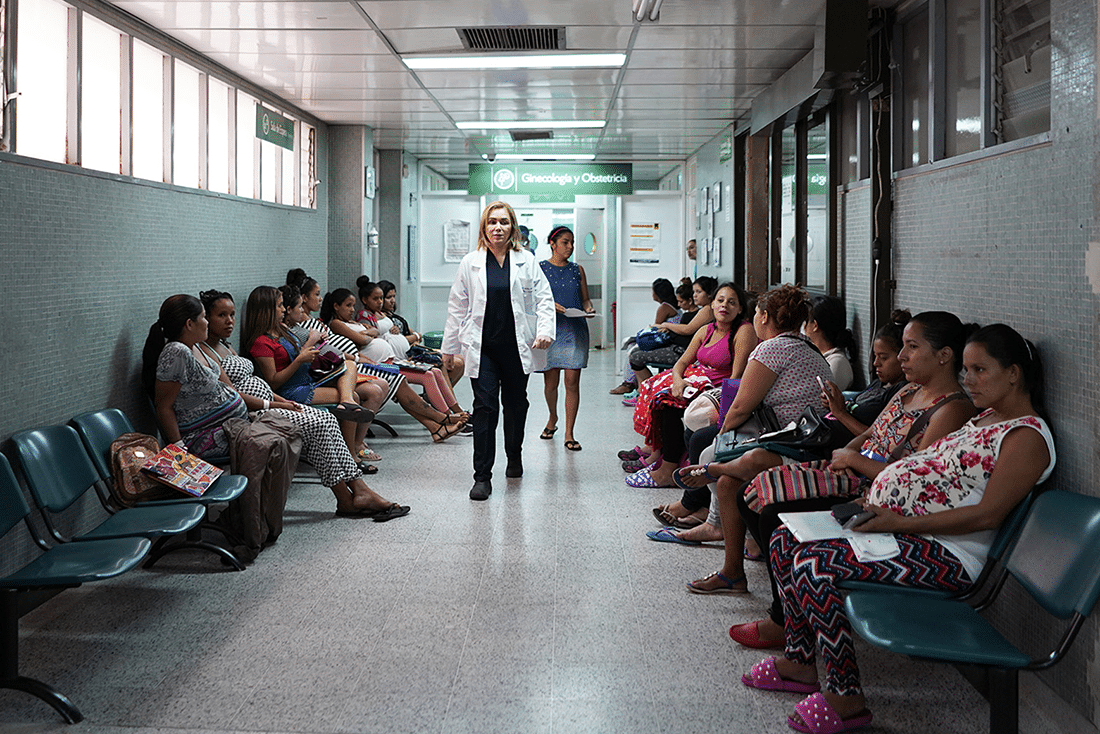

At Erasmo Meoz University Hospital, the only district hospital in the border city of Cúcuta, Project HOPE is providing urgently needed health services to support staff and patients. It’s the only hospital around that will serve Venezuelans and Colombian “returnees” who are uninsured. For many, the hospital is their last resort — their only hope for help.

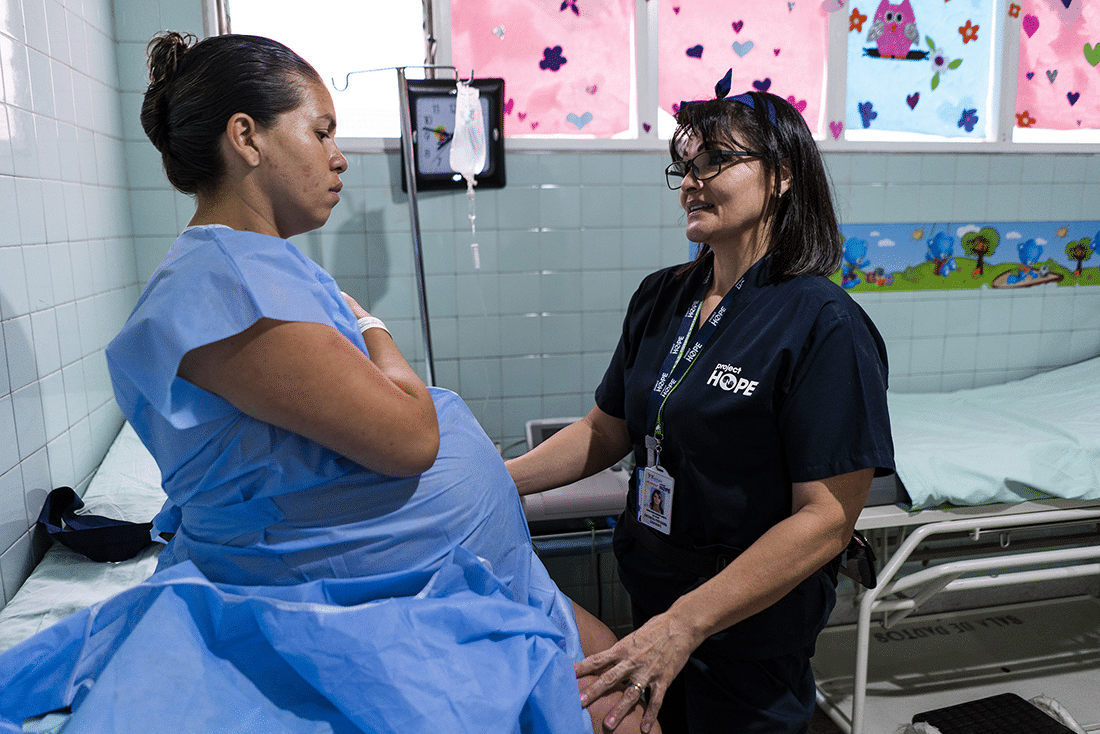

Project HOPE nurses Sandra and Nayra work in the OB/GYN department at the hospital, where they meet dozens of Venezuelan women every day. Colombia has become a destination for Venezuelan women seeking to give birth in a safe environment with the support of trained medical professionals: More than 29,000 babies have been born to Venezuelan mothers since March 2017. Last year alone, more than 8,000 pregnant women who crossed the border were expected to give birth in the country. The majority of these women had not received any prenatal care in Venezuela. Sandra says many of the women they see go into labor before their due date as a result, which puts them at higher risk.

Sandra keeps a daily chart to track the number of Venezuelan and Colombian patients she sees: Most of them are Venezuelan, and some are as young as 14. In fact, most, if not all, of the patients Sandra, Nayra, Dr. José and Dr. Myleidy see are Venezuelan — the majority of them women and children, most of whom are malnourished. Gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases, dengue and skin conditions are most common in the children they see. For women, they usually treat UTIs and chronic diseases and provide prenatal and postnatal care. Cases of diphtheria, malaria and measles are also becoming more common, and the prevalence of hepatitis has increased due to overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions.

The hospital never sleeps. It’s a revolving door of patients going in and out of exam rooms and expecting mothers preparing for delivery. Like clockwork, women who give birth in the morning are discharged in the afternoon, and those who give birth in the afternoon spend one night in the hospital. It’s the longest window of time staff can afford to give each family: The waiting rooms are to capacity — the hallways lined with patients waiting hours to be seen.

“People come with severe health problems such as cancer, HIV and TB, and there are no resources or treatments. Some people end up returning to their countries when they can’t find treatment here.”

– Dr. Myleidy

According to the Human Rights Watch, the number of Venezuelans seeking medical care in this North Santander border area has increased from 182 in 2015 to 5,094 in 2018. To say clinics and hospitals are overwhelmed at this point has become an understatement. “We need more help,” says Dr. Myleidy. “[We need more] people who are willing to provide humanitarian aid. People come with severe health problems such as cancer, HIV and TB, and there are no resources or treatments. Some people end up returning to their countries when they can’t find treatment here.”

For Sandra and Nayra, keeping hope alive for their patients is part of the job. Sandra holds patients’ hands and soothes them during their contractions with a reassuring voice and a soft smile. “I love to be a nurse. I have worked in the hospital for over 25 years and now I am with HOPE. It is a principle in nursing to always take care of patients, which is what we do, and you can actually do even more [working with] a humanitarian organization. It hits your heart when you are working with this type of population.”

“Thanks to Project HOPE’s support, pregnant women are getting quality care services,” says Nayra. “Babies are vaccinated and we provide vaccine cards to make sure they get their follow-up vaccines. We also educate mothers to make sure they learn about how to take care of themselves and their babies.”

Still, Nayra can’t help but worry for the future of the babies they welcome into the world each day. The mothers she sees are usually quite young, and some already have three or four children.