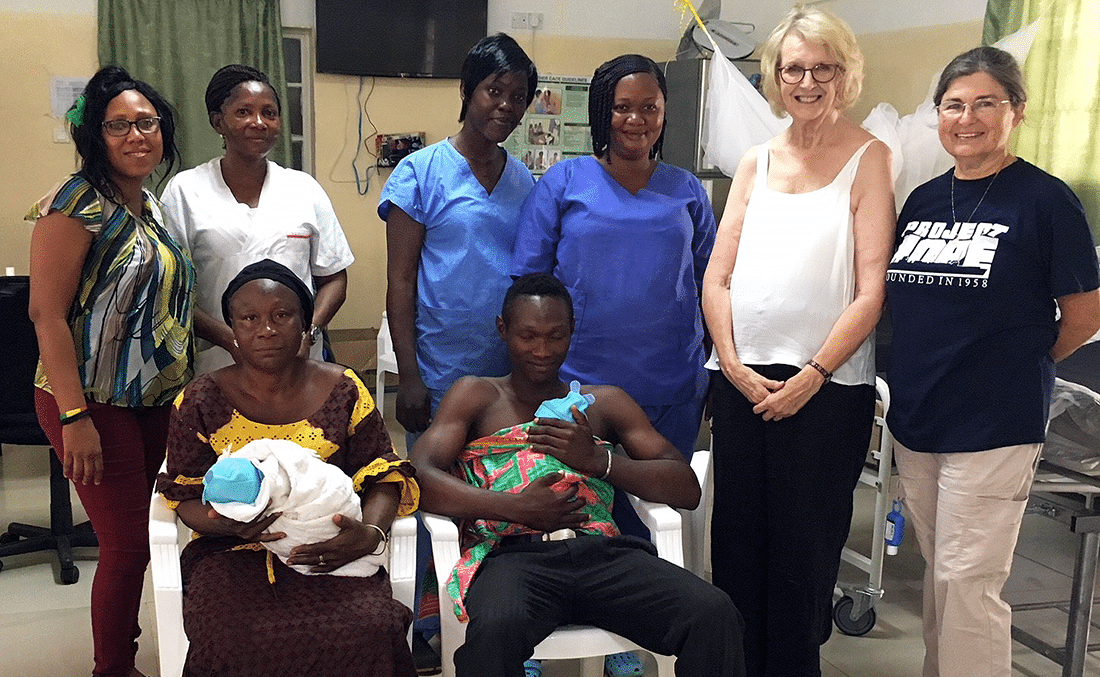

Kangaroo Mother Care Can Be a Family Affair

Project HOPE volunteer teaches families to help their tiny babies thrive

Project HOPE’s Volunteer of the Year Gold Award Winner, Carolyn Kruger, spent 1,200 hours in 2018 focusing her time on nursing education and maternal and neonatal health. Carolyn has worked with Project HOPE as an employee, consultant and volunteer. As a consultant, she developed a maternal newborn child health program in Sierra Leone.

Here she shares just a fraction of her vast Project HOPE experiences.

I wanted to be a nurse when I was 7 years old and that’s what I became. My love for children led me to become a pediatric nurse practitioner. Later I went into academics knowing I could reach even more people by teaching other nurses. My first international health position was director of nursing for Project HOPE. Now that I’m “retired,” the international work I do with Project HOPE continues to feed the need that I have to help people.

This “work” that I do is a joy.

It’s hard for me to think that after all these years there are still such high maternal and newborn mortality rates in countries. I think part of the problem is that there are so many gaps and bottlenecks in underserved communities and health systems around the world. Sometimes communities just aren’t aware of the importance of health.

A continuum of care in Sierra Leone

This is all part of the package that Project HOPE has put together in Sierra Leone. Yes, we work on improving facilities. Yes, we train doctors and nurses in hospital settings. But what happens in the smaller clinics in the village? Are they prepared to save the lives of mothers and their babies who are in distress? What happens when a mother gives birth at home? Is her midwife adequately trained?

In Sierra Leone we look at the approach to health care as a continuum of care and emergency newborn response: we establish mother care groups to improve the referral system, build the community’s trust in the health-care system and extend the reach of services from the community to the household level.

In partnership with Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Project HOPE has provided national and district training programs in the care of small and preterm babies using globally prepared modules such as Essential Care of Every Newborn, Essential Care of Small Babies and Helping Babies to Breathe.

We also established the first two national Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) units for care of pre-term and low birth weight babies.

A simple lifesaving solution

Kangaroo Mother Care is such an effective program for regions with few resources. A baby born prematurely needs special care immediately after birth and throughout the first 28 days. These tiny, fragile babies need constant warmth from their mothers to survive and thrive. The KMC approach places the baby skin-to-skin on the mother’s chest, wrapping the infant securely to the mother for warmth. In health-care facilities without incubators, this method can be a lifesaver. The warmth stimulates regular breathing and promotes breastfeeding for babies who have difficulty breathing and feeding.

These vulnerable infants need to be wrapped KMC-style for 18 to 24 hours a day, potentially for weeks, until they are able to keep their own body heat and can tolerate feeding to increase their weight. Even after the mother is discharged and returns home, she must continue to keep her baby wrapped, even while caring for other children and performing household chores.

Not just for moms

While helping mothers in the hospital KMC unit, we began to invite grandmothers from the waiting room into the unit, teaching them to place and wrap the baby to its mother skin. Eventually, the grandmothers eventually agreed to try the method themselves in order to give the mothers a break.

One day while observing a father hanging around the KMC unit with nothing to do, I asked him if he would try KMC with his son. He was worried about his tiny baby, but he didn’t understand the full purpose of KMC. He smiled shyly and agreed to try, so we wrapped him and supported him while he walked around the unit getting used to having a baby strapped to his chest.

It was clear that he took the entire event very seriously. After that initial exercise, we observed him periodically asking his wife if he could give her breaks, taking the initiative to wrap his son to himself.

Other mothers on the unit watched closely and soon began asking their husbands to do the same thing. The mothers loved this help – it gave them time to bathe and rest.

This has now become part of our regular program. Before mother and baby are discharged, families now have a lesson on KMC care. Once the families leave, KMC-trained community health workers visit them in their homes to check on the baby’s progress.

That first KMC father with his fragile son was soon discharged with a thriving baby who was eating and gaining weight. A follow-up home visit revealed a healthy baby, a father fully bonded to his son and a man who had become a hands-on helper to the rest of the family.