On the Ground: What I Saw Inside a Trauma Ward in Kyiv

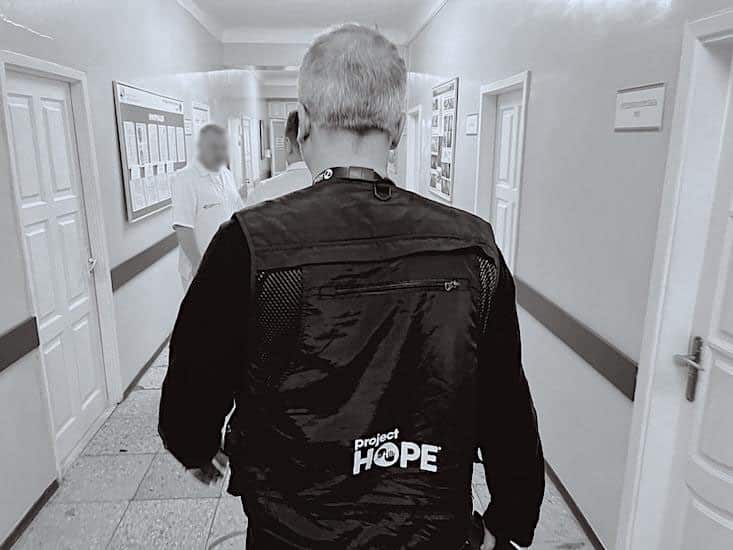

Project HOPE President and CEO Rabih Torbay shares his observations from inside a hospital in Kyiv, where the trauma of war is matched only by the resilience of Ukrainian health workers and citizens.

Project HOPE President and CEO Rabih Torbay was recently on the ground in Ukraine assessing the greatest health needs during the war. You can read another dispatch from his trip here. To learn more about what Project HOPE is doing in Ukraine and how you can help, click here.

We drove straight to the Ukraine border after landing in Krakow. As we waited to cross, we watched few Ukrainians going back. A Project HOPE team member and I helped an older woman who could barely walk with a cane. When I asked why she was going back in, she said she didn’t want to die in a foreign land, and that she had left her only son behind in Ukraine.

We were picked up on the other side of the border and driven to Lviv, a beautiful drive dotted with churches, shrines, and chapels, so distinct and distinguishable. Lviv itself is a beautiful, charming city, though quiet now under curfew. We went to bed early — the next day we would drive 13 hours to Kyiv.

The morning was crisp and cold, and the long drive across the country wound us through quiet, small towns, many of them decorated with Ukrainian flags. The sunrise over the Ukrainian plains was stunning, the morning haze giving way to historic palaces and churches in the distance.

Vast plains of fertile black soil stretched to the horizon, waiting to be planted with wheat and corn. Ukraine is one of the world’s largest exporters of wheat, but there is a major fear that they will not be able to plant enough this year to even meet their own needs. Fuel and diesel depots have been bombed, gas is being rationed, and vast agricultural areas have been mined.

As we approached Kyiv, I noticed that many large trees had been cut down along the road. When I asked why, the answer was sobering: so that the soldiers could have a line of sight should the areas be invaded. It was a stark reminder of how close the war was to the roads we were on.

After navigating multiple checkpoints, we made it to the capital. The streets were deserted, almost everything closed. It was eerily quiet. But then the beauty of Kyiv hit me: the historic buildings, the Motherland Monument towering over the city, the Dnieper River, the churches on almost every hill. We managed to find an open restaurant before the 9 p.m. curfew, happily eating whatever food they were able to serve us before retiring to our empty hotel.

As I went to bed, I made sure the Air Alarm Ukraine app was on, just in case there was a bombing and the aerial attack siren that did not wake me up. Fortunately, it did not go off, and I slept through the night.

The next day, we met with two hospitals in the city. The idea was to assess the greatest needs in the hospitals, both in terms of material and personnel, especially as areas around Kyiv are being liberated and patients are being referred to hospitals in Kyiv.

One of the hospital directors told us how the needs were growing as they received more cases from hospitals in newly liberated areas and the front lines in the northeast. Many of the war wounded were injured weeks ago but did not get proper treatment, either because hospitals were damaged, destroyed, or lacked capacity. Many wounds had developed infections and some had developed gangrene. Doctors had to amputate in some of the cases in order to save the patients.

Some patients had kept the bullets or shrapnel that had been removed from their bodies. Others still had bullets inside them.

The trauma ward was heartbreaking and showed the incredible resilience of the Ukrainian people. We visited many patients who suffered from bullet, shrapnel, and land-mine wounds. The doctors and nurses took their time explaining to us the injuries, the treatments, and how they managed to heal all those broken bones, damaged nerves, and other injuries with limited resources. They were so proud of what they could achieve with so little, and rightly so. Some of the patients had arrived weeks after their injuries, and the staff were doing everything in their power to save whatever they could.

Amazingly, the patients thanked us for visiting them. Some had kept the bullets or shrapnel that had been removed from their bodies. Others still had bullets inside them. The wounded were mostly civilians, including many women and elderly people. Two women in particular moved me. One had lost her leg when an artillery shell fell nearby, severing most of her leg at the thigh and killing three family members. “I’m lucky to be alive,” she told me.

The other woman was in her 60s and had been shot in the arm when she was walking with her hands up. The bullet went through her elbow and triceps, punctured her side, and lodged in her sternum. As she told us her story with tears in her eyes, I think she saw how we were moved. I was tearing up, even though I tried to hide it. She wiped her tears, thanked God and the doctors for her recovery, held my hand in her motherly way, and said proudly in English, “Thank you very much.” I wanted to hug her, but given all the equipment, all I could do was squeeze her hand and smile.

Shortly after, we went back to the doctor’s office. After I thanked him and commended him for the miraculous work he and his team are doing, I asked him, how do they do it? How do they cope with everything they see and deal with?

He began to tear up as he explained that on February 21, the first day of the war, there were few staff in the hospital at 5:30 a.m. But by 10 a.m., all the staff were in the hospital without being called. They all stayed in the hospital 24/7, sleeping on the floor, couches, chairs, empty beds, wherever they could. They divided chores among themselves. They all stayed there together until last week, when the hospital asked them to go back home and look after their families. He showed us photos of all of them celebrating International Women’s Day together. He said he’s never been prouder of being Ukrainian.

As we left the hospital, he escorted us to the door, thanking us again for all the help, for our commitment, and for bearing witness to what they are dealing with.

As we returned to our empty hotel, all of us needed some time on our own to process what we had seen. There was nowhere to get dinner, so we decided walk through the empty streets of Podil, the oldest part of Kyiv. We needed to be reminded of Kyiv’s beauty after having seen the ugliness of war — an ugliness only matched by the incredible resilience of Ukraine’s health workers.

Rabih Torbay is Project HOPE’s President and CEO.